Executive Summary

Iran recognizes the vital role artificial intelligence (AI) will play in its future economic viability, regional influence, and national security and has begun to implement a top-down effort to achieve regional technological competitiveness. Since the Supreme Leader issued a directive in 2021, Iran has endeavored to develop a national strategy and oversight mechanism for AI and foster a technological ecosystem to drive domestic research and development. However, two key factors — Tehran’s global economic isolation, and its deeply entrenched system of government control and oversight — have almost certainly hindered Iran’s national AI development.

In 2024, as Tehran’s support for its proxies Hamas and Hezbollah against Israel embroiled Iran in unprecedented regional conflicts and ongoing cyberwarfare, new insights emerged about how Iran has implemented AI technologies in its national security apparatus. Iran has used AI to bolster its capabilities in four main areas: cyberattacks, influence operations, military and intelligence systems, and domestic repression. These priorities will continue to propel Iran’s development and implementation of AI, almost certainly posing an increasing threat to Iran’s Western and regional adversaries. In cyberspace, AI will likely augment Iranian threat actors’ spearphishing and social engineering tradecraft, while AI’s implementation in Iran’s drone and missile arsenal is likely to pose the greatest physical threat from emerging technology.

Iran’s approach to AI will likely mirror its broader strategic ambitions — to be a regional power and assert its national sovereignty — by building and implementing advanced technological capabilities. Iranian government initiatives are likely to be the driving force behind Iran’s AI development priorities, particularly given the absence of a flourishing AI private sector. While Tehran will promote its own technological prowess and indigenous AI development, the Iranian government is likely to leverage its relationship with China and Russia in various security realms to bolster its AI technology capabilities. Private industry, particularly companies in the AI or technology resources industry, should closely monitor end users of their models or materials to ensure Iranian threat actors are not using their products or acquiring controlled technologies. Similarly, governments should invest in identifying and preventing the Iranian defense industry from acquiring AI technologies that enhance its military capabilities.

Key Findings

- Iran has articulated lofty goals for its AI advancement and seeks to compete in the global AI race, but it is almost certainly hindered by two factors: First, its economic and commercial isolation limits its access to technological resources and human capital. Second, its top-down government control and oversight stifles private innovation in AI.

- To augment its own indigenous research and development (R&D) capabilities in AI, Iran will likely leverage its bilateral and regional relationships for technology engagement with China, Russia, and other non-Western countries.

- Amidst unprecedented domestic upheaval and regional conflict over the last three years, Iran very likely views AI as a key force multiplier for its national security and defense and has sought to integrate AI into its cyber and influence operations, military systems, and domestic surveillance infrastructure.

- It is very likely that Iranian threat actors will increasingly use generative AI and large language models (LLMs) to enhance their influence and cyber operations, increasing risk to adversarial governments, as well as their critical infrastructure, technology companies, and other security-related industries.

- Iran has very likely endeavored to implement AI in its military defense systems and publicly touts the capability, though its operational uses of the technologies remain unproven.

- In the domestic sphere, Iran has very likely increased its efforts to deploy AI for morality enforcement and opposition monitoring, to enhance its control over Iranian society, particularly after the Woman Life Freedom protest movement.

- Companies and governments should maintain vigilance in cybersecurity practices to reduce vulnerabilities to AI-enabled cyber and influence operations and limit Iran’s access to AI resources and expertise that could increase Tehran’s threat to regional security.

Iran’s AI Ambitions

At the highest level of its leadership, Iran has recognized and sought to develop an overarching national focus on AI ( هوش مصنوعی in Persian). In November 2021, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei called AI “an important and futuristic issue” that will “play a role in the future administration of the world,” and urged Iran to become a top ten country in the field of AI. In August 2024, Khamenei urged Iran to “master” and “develop the deep and diverse layers of AI technology,” warning that a global oversight body (similar to the International Atomic Energy Agency [IAEA]) might regulate its use in the future. Khamenei’s stated ambition for Iran’s AI prominence initiated a flurry of government-led activity to develop and implement a national strategy and technological ecosystem to align with the Supreme Leader’s intent. Iran subsequently began creating a national AI roadmap that evaluated the “strategic documents” of 23 countries in the field of AI and developed a plan to realize Khamenei’s goal by 2032. The goals of the roadmap document were to achieve “80 percent of research to meet the needs of the country, use of 45 percent of AI in industries, $8 billion investment in AI, and a 12 percent share of AI in the GDP.” The document contained fourteen “macro policies,” 47 “micro-policies,” 39 “general actions,” and 155 “projects and activities.” According to the roadmap, by the Persian year 1410 (starting March 2031), Iran would need to train 600,000 experts in the AI field to accomplish these objectives.

Iran’s presidency — specifically, the Vice Presidency for Science, Technology and Knowledge-based Economy — oversees the Iranian government’s effort to establish and implement an AI strategy. On December 3, 2023, President Ebrahim Raisi issued an executive order to establish the “National Steering Committee and the National Artificial Intelligence (AI) Center,” which would “focus on creating integrated AI processing and data service providers, aligning with the country’s needs, and implementing large-scale AI projects.” He appointed Reshad Hosseini as Secretary for the Development of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Headquarters, a role intended to develop a “technology development roadmap” and to make “maximum use of all the internal capacity of the innovation ecosystem.” Iran’s AI Strategic Council was to be formed of “ministers and heads of relevant institutions” to “implement, coordinate, and monitor” a National AI Document.

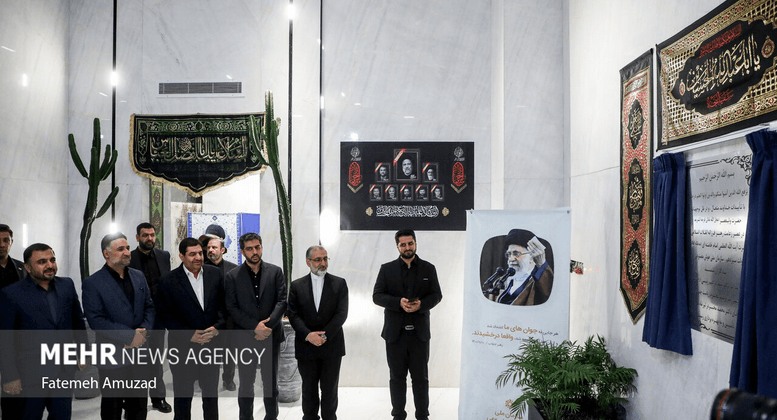

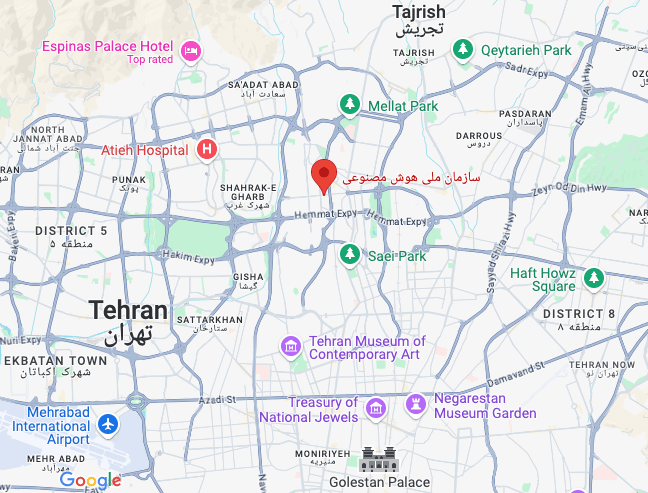

After Raisi’s death in May 2024, the administration of President Masoud Pezeshkian has continued to emphasize Iran’s AI strategy. The National AI Organization (or the National Organization for AI) was inaugurated in July 2024 in Tehran. Insikt Group identified the organization’s physical location in north central Tehran, on Molla Sadra Street (Figures 1-3). During Pezeshkian’s endorsement ceremony and National Government Week meeting in August 2024, Khamenei advised the new administration that the ”good initiative” begun under deceased President Raisi “unfortunately remains unfinished,” but advised that the National AI Organization, under the direct supervision of the President, should continue Raisi’s progress. On October 15, 2024, Iran’s Information Technology Council issued a decision that “within two months, the National Organization of Artificial Intelligence should present to the working group the requirements for creating, developing, maintaining and publishing data and information in the hyper scale database of artificial intelligence.”

Pezeshkian appointed Hossein Afshin, a professor of mechanical engineering at Sharif University of Technology, as his Vice President for Science, Technology, and Knowledge-based Economy, who also serves as the secretary and vice president of the National AI Organization and serves as the face of AI development within Iran. Pezeshkian also assigned his First Vice President, Dr. Mohammad Reza Aref, as chairman of the National AI Organization and its strategic council. Aref’s appointment as First Vice President prompted criticism for his “political obscurity,” likely reflecting Pezeshkian’s choice for the position was based on his scientific prowess and technical acuity rather than his accomplishments as a reformist politician. The prominent role of Aref — who holds two advanced degrees in electrical engineering from Stanford University, has been a professor at two prestigious Iranian universities, and has published scholarly articles on information technology — as Pezeshkian’s deputy with oversight of the country’s AI program suggests an increasing recognition of the importance of AI.

Figure 1: Inauguration of Iran’s National Artificial Intelligence Organization in Tehran

(Source: Mehr News)

Figure 2: Exterior of the National Artificial Intelligence Organization (Source: Google Maps)

Figure 3: Location of the National Artificial Intelligence Organization (Source: Google Maps)

Laying the Foundations of an AI Ecosystem

Insikt Group examined Iranian government statements, press releases, leadership speeches, academic journals, industry websites, and news media, all of which provide key insights into the development and deployment of AI in Iran. However, these sources often provide broad knowledge about Iran’s ambitions or intentions regarding AI and lack details on the specific models, technology, or deployment of AI in support of national security objectives. Western AI companies, such as OpenAI, Google, and Microsoft, as well as global cybersecurity and military experts, offer additional perspectives and analysis of Iran’s AI use cases.

National AI Strategy Development and Challenges

Following its leader’s 2021 directive, the Islamic Republic has striven to develop and integrate AI through the establishment of various bureaucratic entities and industry initiatives. Iran’s progress in AI advancement is almost certainly limited by two factors: (1) its economic and commercial isolation and (2) its government control and oversight. After years of international sanctions and commercial isolation, Iran’s technological advancement, particularly in security-related industries such as defense, energy, and maritime shipping, depends on indigenous and domestically engineered capabilities. Iran strives for self-sufficiency in various sectors, including food and energy, and this concept of a “resistance economy,” which underpins Iranian strategic culture and economic development priorities, very likely shapes the development of Iran’s AI ecosystem. The Iranian government almost certainly disseminates the narrative that Iran is a competitor in an AI global race and seeks to prove its technological prowess. As a result of Iran’s national ambitions for AI, its development ecosystem is very likely government-driven, in partnership with private industry and academia. Iranian technological leaders very likely understand that foreign advances in AI computing power, including private technology companies, can both benefit and augment Iran’s own internal efforts and uses. This dynamic — a top-down national strategy and AI technical development framework that is supported rather than driven by Iran’s own private sector innovation — is likely to limit the potential of Iran’s AI advances.

Iran’s own private sector innovation is likely stifled by its economic isolation and its dependencies on government funding and direction. Iran claims that the government’s expanded support to the tech sector resulted in a surge of Iranian venture capital firms, accelerators, and “innovation centers” between 2019 and 2020, as these firms provided localized solutions amid global supply chain disruption (after the US withdrew from the Iran nuclear agreement and re-imposed sanctions). However, according to a 2022 United Nations report on Iran’s innovation landscape, sanctions significantly hampered Iran’s “startup ecosystem” and the domestic and foreign appetite for investments in Iranian technology startups after 2018 was “reduced substantially.” Iran’s challenges and limitations are reflected in several global indices that analyze and measure AI advances and technological innovation across countries. Stanford University’s Global AI Vibrancy Tool, which defines AI vibrancy as “the level of activity, development, and impact of AI technologies within a country,” does not include Iran in its analysis of 36 countries leading AI-related metrics. Iran is ranked 64th in the Global Innovation Index, which reflects a notable improvement over the last ten years. However, Iran’s institutional, regulatory, and business environments ranked 127th, 131st, and 128th, respectively, underscoring the systemic challenges to Iran’s innovation ecosystem. Oxford Insights ranked Iran 91st of 193 countries in the 2024 “Government AI Readiness Index,” a three-position improvement from its 2023 ranking, but scored lowest in the “vision,” “adaptability,” and “maturity” dimensions.

In 2022, Iran revealed fifteen policies shaping its AI development roadmap. A key theme underpinning these policies was the importance of national research centers, private industries, and universities working together to advance Iran’s AI development. Notably, two of the policies sought to support the private industry’s use of “academic plans” and to increase private industry’s trust in universities, likely suggesting a divide between Iran’s technical industry and its academic institutions. Another key theme of the policies was increasing foreign engagement and cooperation between Iranian and foreign academic centers. This likely reflects Iran’s interest in leveraging foreign partnerships, particularly with countries that are adversarial to the West, in the AI field.

In July 2023, a study from the Journal of Science & Technology Policy found that “the artificial intelligence ecosystem in [Iran] has not yet taken shape in the true sense” and “there is still no relative consensus among actors for dividing tasks and missions.” Less than a year later, the same journal — which is affiliated with Iran’s National Science Policy Research Center — published a Nowruz 1403 (Persian new year, corresponding with March 2024) special edition entitled “Generative Artificial Intelligence: Multiple Perspectives on Opportunities, Challenges, and Implications in Research, Practice, and Policymaking” that examined the “abundant ethical and legal opportunities and challenges” of AI, specifically ChatGPT’s “practical, ethical, semantic, and policy challenges.” The study’s conclusion highlighted the “lack of well-developed ethical guidelines” and noted that it is “vital that new rules be established to govern these instruments, and given their global nature, international coordination is also necessary to maximize their benefits.” The 43 “expert” authors from various business and technological fields disagreed about whether ChatGPT should be restricted or legalized in Iran.

Iran’s bureaucratic challenges in the AI realm, including changes in presidential administrations and a plethora of organizational stakeholders with overlapping responsibilities, likely limit the country’s ability to implement an overarching strategy for its AI development. Tehran’s policy toward AI is overseen by Iran’s Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution (SCCR) — a strategic policy body that answers only to the Supreme Leader — whose approval in June 2024 was required to move forward with the National AI Organization, steering council, and the document’s “generalities.” This approval involved review of the AI organization’s statutes and 18,000 supporting documents to ensure the project was not “tainted by Western influence.” The SCCR established a specialized Commission for AI in September 2022 composed of officials from all armed forces branches, the General Staff of the Armed Forces, the Office of the Supreme Leader, the Ministry of Intelligence, and the Ministry of Higher Education. In January 2025, Pezeshkian noted the importance of AI development in a meeting with the SCCR, asserting that “any delay or backwardness in the development of AI in Iran would be damaging and irreparable.” Domestic critics of Iran’s AI policy have raised concerns about the “unstable decisions, constant policy changes, and lack of a clear roadmap” that has hampered the country’s AI program. For example, in December 2024, Afshin announced that the cabinet was drafting a charter for the National AI Organization that would focus on the organization’s role in planning and overseeing AI activities; three months later, semi-official news agency Tasnim News suggested the possibility that the National AI Organization could be dissolved, raising a “series of contradictions” and “unanswered ambiguity.”

AI Budget

Documentation of Iran’s investment and funding of AI is opaque, but even with conflicting information, Iran’s lack of significant AI funding compared to its competitors will likely imperil its top-ten AI ambitions. The SCCR reportedly allocated a budget totaling 3.5 trillion Tomans (“over 83 million dollars”) in its approval; Iran’s initial operating budget for AI has also been reported as $50 million USD. According to the Tehran Times, 50 trillion rials (“some $100 million”) has been allocated for the development of AI operators during Persian year 1403 (between March 2024 and March 2025). In January 2025, Iran’s National Development Fund — independent of the Iranian government budget — agreed to allocate $15.6 million USD to AI projects in universities and private research centers, while another $100 million USD will be provided in the form of loans. These funding numbers lag significantly behind the AI budgets of regional competitors like the United Arab Emirates (approximately $1.2 billion USD) and Saudi Arabia (approximately $2 billion USD).

Government Entities

Insikt Group identified a number of government entities that are involved in the direction, strategic planning, and national coordination for the development of Iran’s AI capabilities. The protracted process for the formulation of Iran’s national AI strategy document, which has involved a cross-agency collaboration process with multiple stakeholders, likely reflects a bureaucratic competition for influence and ownership of AI leadership within the Iranian government. The division of power among various government elements has likely hampered Iran’s ability to form a cohesive AI strategy and development plan.

| Organization | Role in AI Development |

| Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution (SCCR) |

|

| Vice Presidency for Science, Technology and Knowledge-based Economy |

|

| National Artificial Intelligence Organization (or National Organization for AI) |

|

| Ministry of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) |

|

| ICT Research Institute (Formerly ITRC) |

|

| Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Development Center |

|

| National Cyberspace Center |

|

Table 1: Iranian entities involved in AI strategy (Source: Recorded Future)

Iran’s military plays a key role in technological developments through civil-military cooperation, which very likely extends into the AI realm. Iranian armed forces, including the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), have affiliated universities and science and technology (S&T) parks and run their own technology parks as “incubators.” For example, Imam Hossein University — affiliated with the IRGC — has a technology center and hosted “The International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and the Future Civilization” on January 29, 2025. Iran’s military branches from the Army and IRGC’s ground, naval, and air forces each have their own research and development entity, referred to as a Research Self-Sufficiency and Jihad Organization (RSSJO), that conducts specialized and tailored R&D for the unique needs of their respective forces. These RSSJOs are likely involved in independent efforts in defense-related R&D and in cooperation with academic institutions; they are likely integrating AI development into those efforts. Iran’s Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL) also likely has a key role in defense-related AI development, having signed partnership agreements with 80 universities and 800 industrial towns in Iran.

Government Initiatives

Announcements by the Vice Presidency for Science, Technology and Knowledge-based Economy regarding its AI development initiatives likely suggest Iran is working to develop a sovereign AI capability — meaning an Iranian national capability to produce AI using its own infrastructure, data, workforce, and business networks through the development of foundation models trained on local datasets that reflect local language and culture. Hossein Afshin, Iran’s Vice President for Science, Technology and Knowledge-based Economy, hosted a meeting with the “Technology Group” from Tarbiat Modarres University on December 1, 2024, during which he reviewed the team’s progress, requirements, and support mechanisms for its “Project for Designing a Large Native Iranian Language Model.” He subsequently announced on December 3, 2024, that a prototype of Iran’s “national AI operating system,” which was “designed to host AI algorithms locally,” was expected in six months. Iran intends to launch the country’s first GPU data center by 2025 and plans to establish its first AI park — to “showcase the technological developments of the country and provide practical AI-related services to the people” — within the next two years.

On March 15, 2025, Vice President Afshin unveiled Iran’s national AI platform and announced a phased rollout of the project, framing it as a strategic move in a global “war of chips and algorithms.” The platform’s initial testing and optimization are planned for the first half of 2025, followed by limited access for technology experts and companies in the third quarter, a public beta release in September 2025, culminating with a public release in approximately March 2026. Over 100 Iranian professors and researchers collaborated on the project, which was developed in cooperation with Sharif University of Technology — an institution that is sanctioned for its links to the IRGC and MODAFL related to military and ballistic missile technology development. An expert developer and representative of Sharif University, Hossein Asadi, noted that the AI platform was developed using an open-source framework and specifically highlighted that it would be “entirely independent, with no reliance on foreign APIs [application programming interfaces],” ensuring the platform’s services would continue without disruption “even if the country’s internet were to be completely disconnected.”

Iran almost certainly seeks to leverage domestic resources to support these development initiatives. On December 13, 2024, Afshin declared the government’s intention to jumpstart domestic chip production for AI through the “Sahand National Project” (“پروژه ملی سهند”). The Sahand National Project is consistent with Iran’s focus on leveraging its own human and natural resources to deliver indigenous technological solutions and is likely a reaction to an anticipated increase in economic isolation under the US presidential administration of Donald Trump. The US government announced export restrictions on January 13, 2025, which are designed to curtail the sale of chips with high-computational graphics processing unit (GPU) power for AI advanced development (such as Nvidia’s A100 and H100 chips) to sanctioned countries like Iran.

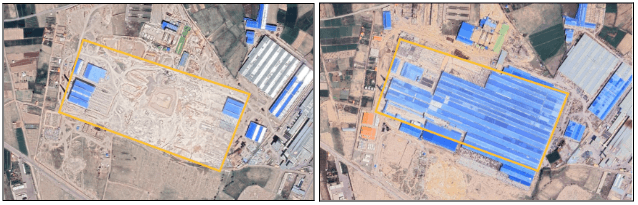

According to Iranian media, the project’s aim is to manufacture “nine-nines” (99.9999999%) purity silicon wafers, the first step in setting up a domestic supply chain for microchips, with a view to open Iran’s first GPU data center by “early 2025.” While public information on the project remains limited, its reported location — in Sahand, East Azerbaijan province — would likely have been chosen for its proximity to Sahand Industrial Group (SIG), Iran’s leading glass and silica producer, and the Sahand University of Technology, which has specialized laboratories in material and nanomaterial engineering. Using satellite imagery, Insikt Group identified a new two-million-square-foot facility under construction near an existing SIG silica manufacturing plant in Sahand, showing significant investment in the region’s industrial capabilities.

Figure 4: Satellite imagery of a two-million square foot facility between May 2020 and May 2024 near an SIG silica plant in Sahand, East Azerbaijan, Iran (Source: Google Earth)

Another government initiative announced on January 11, 2025, by Afshin aims to establish a hub for AI innovation in the oil and gas industries on Kish Island, Southern Iran, in association with the Persian Gulf Petrochemical Industries Company and the Kish Free Zone Organization. The location choice likely enables the Iranian government to unlock three benefits for the acceleration of AI development: the Kish Free Zone’s lax foreign investment and fiscal policies to encourage foreign direct investments (FDI); existing infrastructure, including an international airport and ports that can be leveraged for international transit; and lax entry visa requirements on Kish Island that enable reputable Iranian academic institutions (such as Sharif University of Technology, which has an international campus in Kish) to attract foreign talent and investment.

Iran has announced several AI-enabled tools for the benefit of the Iranian government and society. Alongside his announcement of Iran’s domestic chip production project in December 2024, Afshin also declared that the Iranian government has prioritized the development of “AI assistants” available to government officials, developed “in collaboration with universities” with a team of over “70 expert professors.” The AI assistants are reportedly expected to help government ministers to “extract both laws and regulations and production-related issues from data” and “make suggestions in decision-making.” In August 2024, Iran’s National Cyberspace Center announced the Arbaeen Artificial Intelligence Assistant (which references Arbaeen, a Shi’ite holy day, during which Shi’a Muslims make a pilgrimage to Iraq) was “a guide for pilgrims to access routes and processions, management of information for scheduling ceremonies and events, as well as the status of health and medical services, weather conditions, and even cultural and linguistic guidance online.” In November 2024, Iran’s national religious headquarters, located at Qom Seminary, launched an “indigenously developed platform that uses AI to answer questions and remove doubts on religious issues.” Dubbed Deendaan, the platform was introduced by the seminary’s National Center for Answering Religious Questions. Another entity in Qom, the Noor Computer Centre for Islamic Sciences Research, is seeking to incorporate AI in its use of religious texts and data to “accelerate the Islamic studies of senior clergy and speed up their communication to the public.”

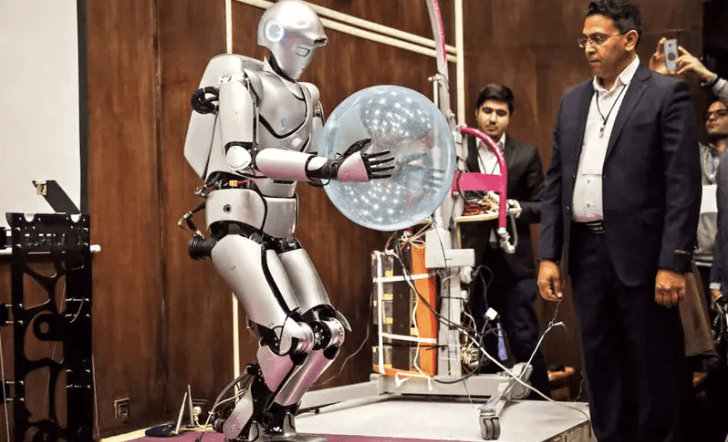

Academia

Iran’s most globally recognized AI innovation, the Surena IV humanoid robot, was developed by Iran’s academic sector, underscoring the key role of universities and research institutes in Iran’s AI ecosystem. Created at the Center of Advanced Systems and Technologies (CAST) at the University of Tehran, the robot’s fourth generation uses the “Robot Operating System” for “state monitoring, real time implementation of algorithms, and simultaneous running of several programs.” The robot was listed as one of the top ten humanoid robots in 2020, according to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. In addition to developing the Surena humanoid, CAST has a “portfolio” of projects related to various fields, including “mechatronics, robotics, and intelligent systems inspired by nature,” as well as “aquatic inspired” robots and those “inspired by birds.”

Figure 5: Surena IV, developed at the University of Tehran (Source: IEEE)

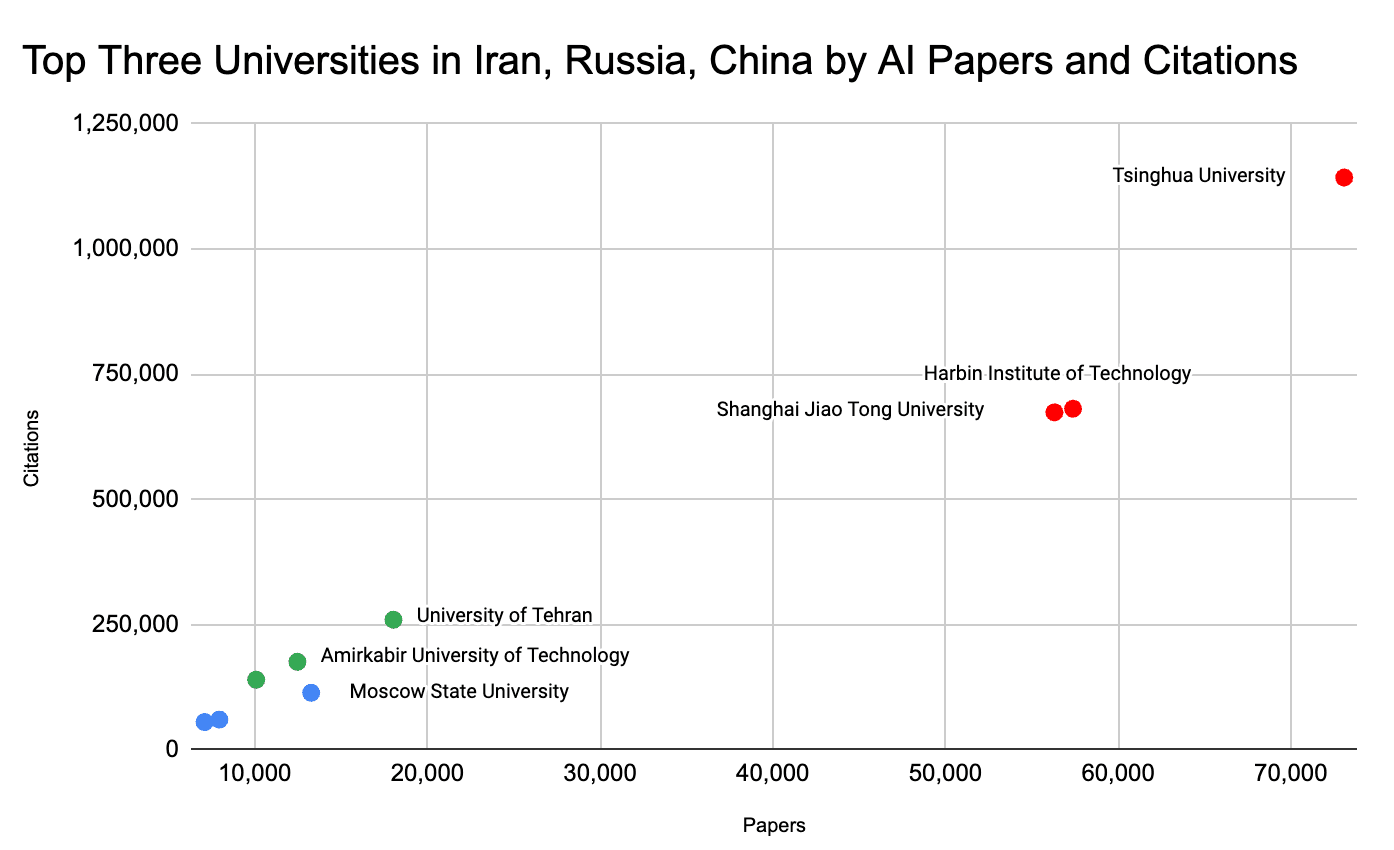

Leading Iranian universities in the field of AI include the University of Tehran, Amirkabir University of Technology, and Iran University of Science and Technology, all located in Tehran. According to the state-run news outlet Tehran Times, over the last ten years, the most “scientific productions” in artificial intelligence have been associated with Tehran University, Tabriz University, and Amirkabir University of Technology. However, these universities likely remain low on global rankings for AI research; the University of Tehran, widely recognized as the best higher education institution in Iran, ranks at number 201 globally for AI. Edurank data suggests that Iran’s top three universities are ahead or on par with their Russian peers (Moscow State University, St. Petersburg State University, and the National Research University) but far behind China (Tsinghua University, Harbin Institute of Technology, and Shanghai Jiao Tong University) in terms of production (number of publications) and influence (number of citations). Iranian national investment in AI research is likely less than Russian investment, but its academic citation numbers are greater than Russia’s, likely reflecting that Iran’s AI academics maintain disproportionate influence in their field relative to their Russian counterparts.

Figure 6: Top three universities in Iran, Russia, and China by papers and citations in the field of AI (Source: Edurank)

In the absence of a vibrant private AI sector, the Iranian government is likely reliant on academics specialized in AI for government projects at the expense of cutting-edge research. Iranian media boasted that “70 expert professors” were working to design an AI platform for government ministers. Sharif University of Technology, ranked fourth in Iran in AI, is likely a key partner for government projects, such as Iran’s national AI platform. The government demand for expertise likely represents a misallocation of research talent towards state-mandated engineering projects, which likely impedes Iran’s research potential. However, Iranian academic centers may also be exploring open-source AI development, which likely encourages innovation. For example, in November 2024, Amirkabir University, in collaboration with AI developer Part AI, announced the development of the “most comprehensive and powerful evaluation system for Persian language models,” known as Open Persian LLM Leaderboard, which includes over 40,000 samples and tracks the performance of 25 major open-source models at Persian-language tasks. Part AI has also published six open-source models, including Persian finetunes of Meta’s Llama 3.1 and Google’s BERT models.

A search of recent and upcoming conferences related to AI suggests Iran’s academic sector is exploring AI applications in several sectors, including medical sciences, telecommunications, electrical engineering, education, mining, and industry. In 2024, Iran held a number of inaugural national conferences on specific topics, very likely suggesting the concept of how AI can benefit specific industrial sectors is still nascent in Iran. For example, in October 2024, Iran held the first national conference on AI in education and learning; in May 2024, Iran held its first national conference on AI and the Internet of Things; in April 2024, it held its second national conference on Digital Transformation and Intelligent Systems.

Figure 7: Poster of international AI conference which notes the cooperation “with prestigious universities and scientific centers of Iran and the world” (Source: Imam Hossein University)

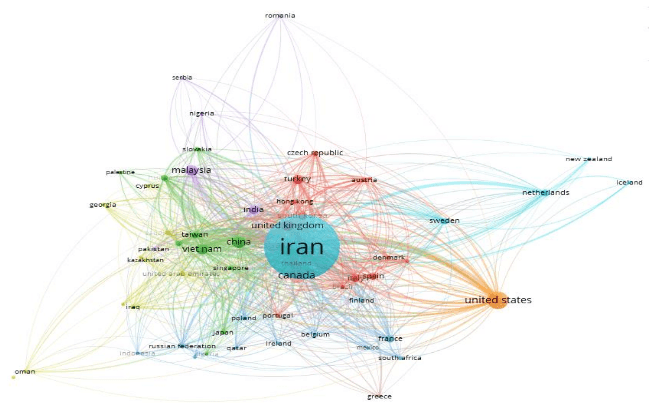

Iranian universities are very likely driving international engagement by hosting conferences on AI. A review of international AI-related conferences held in Iran in 2024 and planned for 2025 highlights a wide range of foreign academic participants, including academics from Austria, Australia, Canada, China, France, Italy, Iraq, Malaysia, Russia, Spain, Vietnam, and the United Kingdom. Iranian academic output on AI likely benefits from strong ties with Iranian-American researchers and collaboration with US academic institutions. An Iranian study of domestic output of AI research between 1978 and 2022 found that US researchers were the most frequent international co-authors on Iranian AI research. However, Iranian academic AI research likely remains of limited international influence. 19.9% of Iranian AI papers during this period received no citations, with the majority receiving between one and five citations.

Figure 8: Network map of countries co-authoring with Iranian AI researchers between 1978 and 2022, based on the Scopus database (Source: Shahed University)

Private Technology Companies

Iran’s private sector currently faces significant challenges in the face of international sanctions and lack of global competitiveness, including the inability to retain top talent, the absence of foundational AI model companies, low capital expenditures on AI by existing major players in the technology sphere, and a nascent venture capital (VC) ecosystem.

Iran almost certainly suffers from a significant talent outflow of skilled workers in technology and AI. According to a 2021 report by the Iran Migration Observatory, 50% of Iranians involved in startup communities and 44% of graduates were planning on emigrating, citing unpredictable internet regulations, censorship, and lack of wage competitiveness as direct factors. In December 2024, Iran’s Vice President Afshin announced a new regulation offering monthly grants of approximately 15 million Tomans ($3,564 USD) for PhD students to encourage research and scientific activities, stressing the importance of preventing talent migration.

Despite talent shortages, Indian data provider TraxCN has identified at least 85 companies in Iran advertised as operating in the field of AI, with a majority focusing on developing AI enterprise applications and tools for healthcare, agriculture, and finance. Several companies provide chatbot services and LLMs, including Persian-language chatbots; however, it remains unclear whether they are developing proprietary models rather than deploying existing open-source models. Additionally, TraxCN considers that seventeen (20%) of these companies are currently “deadpooled” (no longer in business) and 60 (80.5%) remain unfunded, indicating that despite government efforts to incentivize AI startups, the average Iranian AI startup is doomed to fail in raising funds or operating sustainably. Iranian AI website Hooshio published a list of 29 Iranian AI companies, highlighting the Parth AI Research Center as “one of the top five companies in the Middle East” with more than 150 specialists in AI. The company claims to have Iran’s “biggest AI research center” with a department for machine vision, natural language processing (NLP), speech processing, and data analysis, as well as an AI college.

Iran’s private tech sector is likely trying to financially motivate AI innovation and engage with Iran’s developer community. Digikala, Iran’s biggest technology and e-commerce company (valued at approximately $500 million USD as of August 2024), hosted an AI hackathon in March 2024 with a first-place prize of 60 million Tomans (approximately $14,258 USD). Notably, the hackathon’s rules banned participants from using Western AI models (listing models from Western companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Cohere), likely intending for participants to focus on using open-source models for hackathon entries.

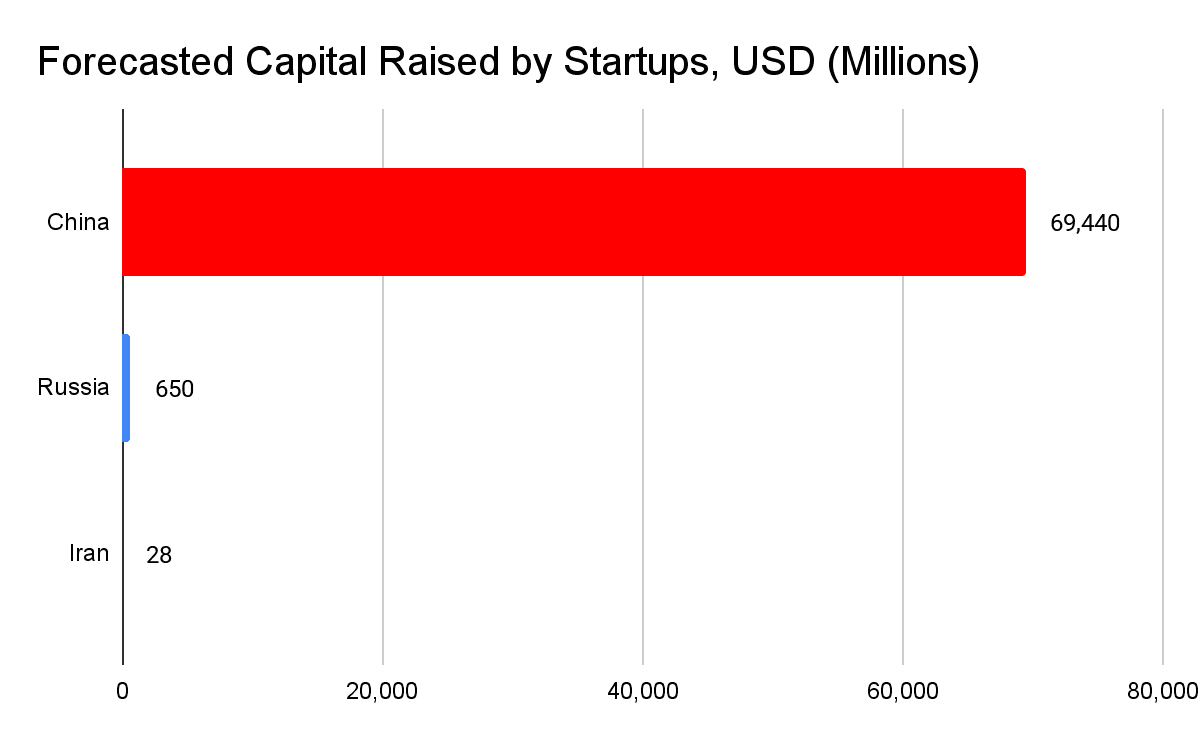

Unlike their Western and Chinese counterparts, Iranian VC funds are likely limited in their ability to fund and support a domestic AI startup ecosystem to fulfill national security and economic priorities, with startups forecasted to raise $28.13 million USD in capital in 2025 across all sectors. Iran’s Pardis Technology Park (PTP), dubbed “Iran Silicon Valley” and operating “under the auspices of” the Vice Presidency for Science, Technology, and Knowledge-based Economy, is “the most significant center for developing startups and knowledge-based companies and commercialization of technology and innovations in Iran.” PTP, which is part of the Iran International Innovation District, boasts 25.5 million EUR of foreign investments in its companies over the last five years and is also supported by the Iran National Innovation Fund, Iran’s version of a venture capital and private equity firm.

Figure 9: Forecasted capital raised by startups for 2025 in China, Russia, and Iran (Source: Statista 1, 2, 3)

Open Source

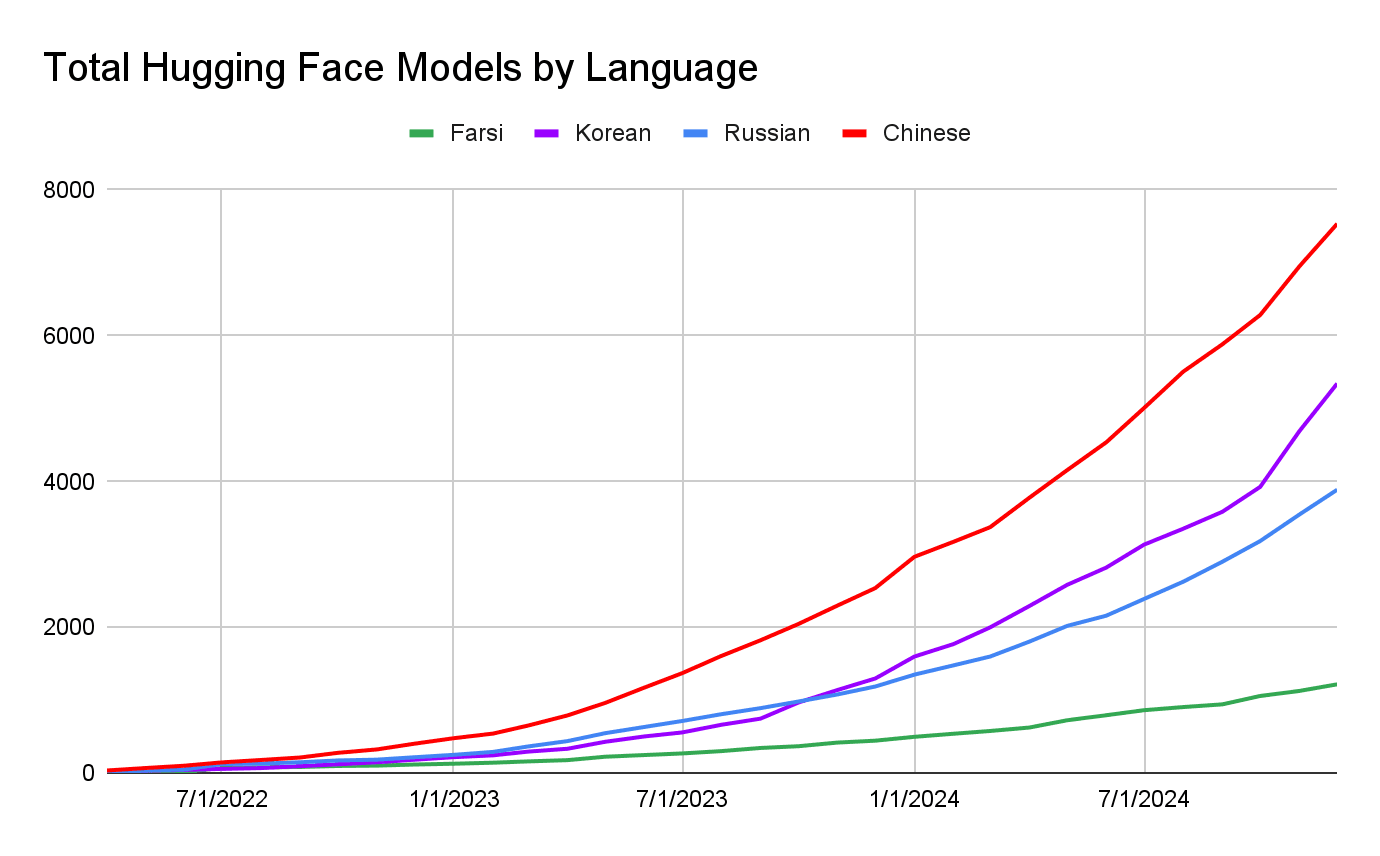

Open-source communities play an important role in the development of AI capabilities, as open-source AI models can lower research and development costs, present opportunities for technology transfers, and reduce dependency on models developed by foreign companies. Iran’s open-source community almost certainly lags behind in terms of developing home-grown AI models, finetunes, and datasets. Data from open-source AI model platform HuggingFace shows that Farsi-language models (including multilingual models from US AI companies) are outnumbered by open-source models with language capabilities for Mandarin, Korean, or Russian. Sanctions are almost certainly throttling the emergence of a strong Iranian open-source software community. GitHub, a major platform for hosting open-source code, was blocked in Iran in 2019 and only resumed operations in 2021 after securing a special license from the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) board.

Figure 10: Number of models published on HuggingFace with language capabilities in Farsi, Russian, Korean, and Chinese (Source: HuggingFace)

Iran’s biggest open-source AI contributor, measured by the number of Farsi-language AI models published on Hugging Face, is likely Hezar AI, followed by Persian NLP and Hooshvare Research Lab. US technology companies Facebook and Google are also among the top ten publishers of Farsi-language models on HuggingFace.

Foreign Cooperation

Iran’s Organization for Development of International Science and Technology Cooperation (ODISTC) very likely plays a critical role in facilitating the exchange of ideas, goods, and services related to AI. ODISTC was set up “to serve as a foundation for increasing scientific, technological and innovation communications with other countries, as well as securing a significant share of the regional and global trade of knowledge-based products.” Among the services offered in ODISTC’s “Technological Exchange Office” is “bilateral scientific and technology cooperation in the form of joint research funds with the [sic] countries like China and Russia.” More details pertaining to Iran’s cooperation with China and Russia are discussed below.

China

Iran’s technological cooperation with China is very likely a key strategic interest for Iran’s AI development. In 2021, Iran’s Strategic Council on Foreign Relations promoted building relationships between Iranian and Chinese technology companies and higher education institutions. AI was specifically mentioned as part of the Iran-China 25-year Comprehensive Partnership, officially signed in March 2021. A leaked version of the plan, sourced from Iran’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and reported by the Wilson Center, proposed the cooperation involved “introducing joint pilot projects in the fields of smart technology and artificial intelligence.” Second to the sale of its oil to China, Iran likely views AI development and technological exchanges as a top priority for its bilateral relations with China, and China’s challenge to US dominance in AI development aligns with Tehran’s goal to oppose US hegemony.

China’s use of AI for surveillance and monitoring has very likely been the most robust area for Iran’s foreign AI engagement, enabling Chinese companies to expand their export of specific technologies that facilitate Iranian domestic repression. However, academic and research collaboration is very likely another key area in which Iran’s technology sector is benefitting from the relationship with China. In November 2024, Iranian company Bayan Rayan — the country’s only server producer — received an award at the 26th annual China Hi-Tech Fair (CHTF) 2024. In 2022, an official at Iran’s Islamic Azad University touted the Iran-China agreement as a “golden opportunity to boost cooperation in AI” and benefit from Chinese advancement in the AI field, noting that Iran had 3,000 Iranian students studying in China.

Russia

The anti-West strategic alignment and commercial isolation that Iran and Russia both share, particularly as a result of Russia’s war with Ukraine, has resulted in deeper cooperation in many security-related fields. Despite the increased cooperation in several spheres, specific details on the extent of the current Iran-Russia collaboration on AI R&D are limited. In January 2025, Tehran and Moscow signed a comprehensive twenty-year strategic partnership agreement that reinforced areas of ongoing cooperation in the technical sphere, including information and communication technologies, digital development, and higher education. While the text of the agreement does not specifically mention AI, Iran’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated the agreement “provides a platform for sharing knowledge and collaboration in fields such as nanotechnology, aerospace, artificial intelligence, and medical sciences” and expands cooperation at the government and academic levels.

Leading up to the 2025 comprehensive agreement, a flurry of Iran-Russia cooperation documents and engagements have promoted cooperation on AI. In March 2024, the two countries signed a Memorandum of Understanding to cooperate on ethics in AI, “exchanging experiences in the implementation of the ethical principles of AI.” The agreement specified that the Russian Commission on Ethics in AI would provide training for Iran’s AI and Robotics Development headquarters. In November 2019, Russia and Iran signed a Memorandum of Understanding on cooperation to support twenty joint research plans in fifteen scientific fields, including, among others, information technology, computer systems, and AI.

To read the entire analysis, click here to download the report as a PDF.